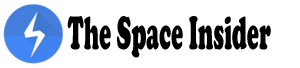

2,000-Year-Old Skull Shows Evidence of Ancient Surgery

A skull housed at The Museum of Osteology in Oklahoma has caused quite the stir in the archeology community. The 2,000-year-old skull of a Peruvian warrior is thought to be one of the world’s oldest examples of advanced surgery.

The skull of a Peruvian warrior who has a metal plate on their skull. (Photo Credit: Museum of Osteology)

Experts believe that the warrior sustained this head wound during battle. When the warrior was brought back from war, Peruvian surgeons implanted a piece of metal in his head to help heal the injury. Miraculously, the warrior survived both his injury and this surgery.

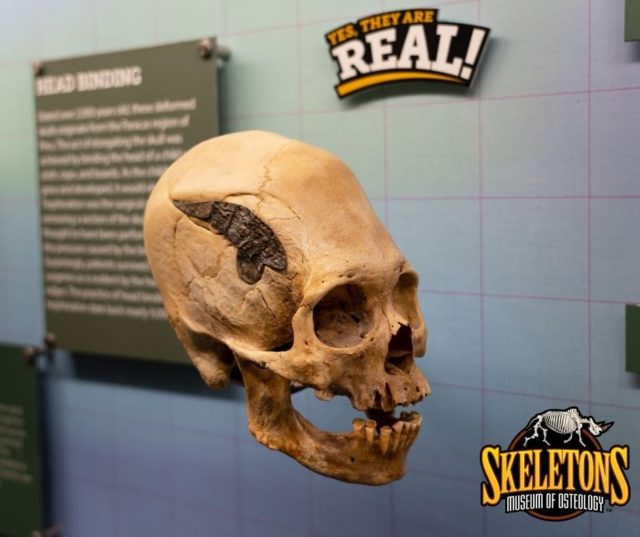

This remarkable specimen is an example of a Peruvian elongated skull. Skull elongation is an ancient form of body modification practiced in cultures throughout Western Europe, the Americas, the Far East, and Africa. This was a practice that showed social status in the Americas. To achieve this look, a baby’s head would be bound with bandages, or secured between two wooden plates, to distort its growth.

(Photo Credit: Museum of Osteology)

It is astonishing that the warrior survived the surgery to begin with, but also when we factor in that there was no real anesthesia at the time. In a Facebook post, the Museum of Osteology points out how tightly the broken bone surrounding the repair is fused together, which indicates a successful surgery.

In another Facebook post, the Museum writes that “although we can’t guarantee anesthesia was used, we do know that many natural remedies existed for surgical procedures during this time.”

The Museum also stresses that the material was not poured into this warrior’s skull as molten metal. A spokesperson for the Museum told the Daily Star, “We don’t know the metal. Traditionally, silver or gold was used for this type of procedure.”

(Photo Credit: Museum of Osteology)

Head injuries were fairly commonplace in Peru thousands of years ago. Projectiles like slingshots were used during battles, which caused terrible head injuries. Peruvian physicians must have found a way to deal with these wounds. In fact, according to John Verano, a physical anthropologist at Tulane University, the survival rate of these procedures was surprisingly high, at about a 70% success rate.

The skull is currently on display for the public at the Museum of Osteology in Oklahoma.